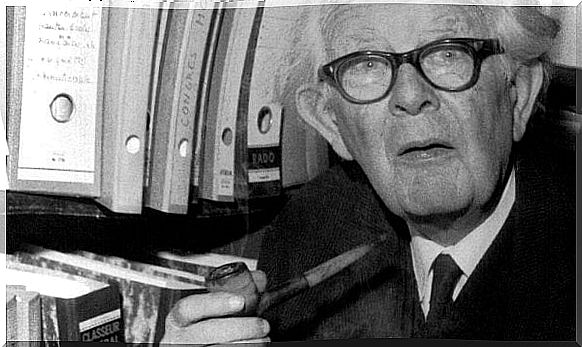

The Cognitive Development Of Children According To Piaget

Jean Piaget is an essential reference point in the study of children’s cognitive development. He devoted his entire life to studying his childhood, even that of his own children, to uncover the secrets of development. He is also known, along with Lev Vygotsky, as one of the fathers of constructivism.

One of Jean Piaget’s most famous theories is his cognitive development theory, in which he formulated four different stages in child development. He devised this in order to arrive at a theory that would explain the general development of a child.

However, we now know that his theory ignores too many aspects to be accepted as a theory of general development. Nevertheless, this classification is a useful guide to understanding how we develop our logical-arithmetic abilities in childhood.

The stages of children’s cognitive development

Many psychologists believed that development was an accumulative phenomenon, generating new behavior and cognitive processes.

Piaget, on the other hand, after his research formulated a theory of development based on qualitative leaps forward. Here the child would acquire capacities, but sooner or later that accumulation would qualitatively change his way of thinking.

Piaget initially divided the child’s cognitive development into three phases with a series of sub-phases, later becoming four. These four stages are: (a) sensorimotor stage, (b) preoperational stage, (c) concrete operational stage, and (d) formal operational stage.

sensorimotor phase

This phase precedes speech development and lasts from birth to about the second year of life. This period is characterized by the child’s ability to control reflexes.

During this period, the child learns to respond motorically to what it perceives. In his head there are only practical concepts such as knowing what to do, what to eat or how to get his mother’s attention.

Little by little, the child generalizes the events in his environment and creates ideas about how the world works.

As these ideas intersect, the child develops the idea of permanence of objects and understands that objects exist as entities foreign to him.

Until this idea is developed, things exist for the child only if he can see, hear or touch them. If he can’t do this, then they don’t exist as far as he’s concerned.

The end of this phase is marked by speech development. Developing speech involves a profound change in the child’s cognitive skills.

This is usually associated with the semiotic function: the ability to represent concepts through thought. The child would go from a purely practical mind to a mind that also acts on a representative level.

Preoperational Phase

This phase occurs between the second and seventh year of life. Here we are in a transition period where the child begins to work with his semiotic ability.

Although he is already somewhat capable of seeing things from different angles, his mind is still very different from that of an adult. Here we come face to face with his “egocentricity.”

The child is “egocentric” because his thinking is completely egocentric. The child cannot distinguish the physical from the psychic, nor the objective from the subjective.

For him, his subjective experience is the objective reality that exists in the same way for all individuals. This shows us something that is still missing from the Theory of mind. From the fourth year of life, the child begins to lose this egocentricity and learns that his own views, desires and feelings may differ from those of another.

We also see problems at this stage. The child must be able to understand that the universe is changing. He can understand states, but not the transformation of matter. His thinking is therefore focused on one dimension.

An example of this is when a child is shown a glass of water at this stage, the contents of which are then poured into a narrower but taller glass. The child will think there is more water than before. It is unable to understand that transforming something does not change the amount of existing matter.

Concrete operational phase

This period includes the years between the seventh and the eleventh or twelfth year of life. At this stage, the child has managed to leave behind him the full confidence he had in his senses. Here we can see the development of concepts, including the ability to understand that changing the form of something does not change its quantity.

The child begins to construct a logic of classes and relationships unrelated to perceptual data. The child understands changes and understands that they can also occur in the opposite direction (add instead of delete, for example).

And an important aspect is that he can perform these actions in his mind, without the need for concrete material to be present.

Although he is able to perform certain actions and logical activities, he can only perform them with specific objects with which he is familiar. He cannot theorize about what he does not know or what is beyond his perceptual knowledge. The child develops this skill in the next stage.

Formal operational phase

This is the final stage of development, in which the child will become an adult on a cognitive level. This stage is characterized by the acquisition of scientific thinking. While the child can reason about real things, he can now reason about the possible.

This period is characterized by the ability to make hypotheses and explore the possible consequences of these hypothetical possibilities. The child has perfected his testing procedures and does not accept opinions without examining them.

The child begins to acquire new knowledge and intellectual resources. This allows him to develop as a competent adult in society.

However, from this point on, he will not make any other qualitative leap.

He may become faster or more precise with his mental activities, but he will still think the same way.

What do you think of Piaget’s cognitive development theory? Does this theory fall short when it comes to explaining human development as a whole?